Yr a Oydo — The Liner Notes

Here is Vicente Parrilla’s essay –reproduced in full– included in the liner notes of Yr a oydo, our latest CD.

We thought it useful to present the text here as well so that it’s more easily accessible.[^1]

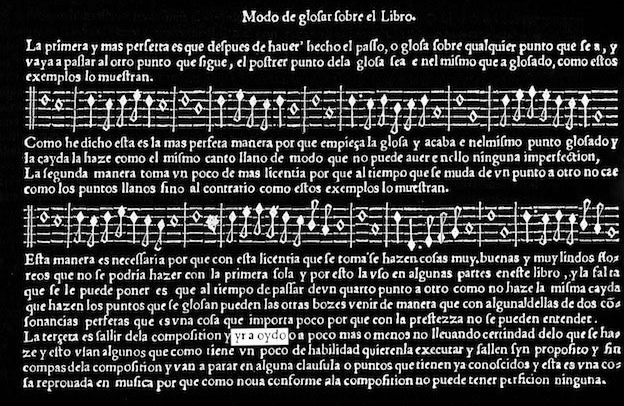

“La terçera [manera] es sallir dela composition y yr a oydo, o a poco más o menos, no llevando certindad delo que se haze”.

—Diego Ortiz, Trattado de Glosas, Rome 1553. Modo de glosar sobre el libro

1. The Impulse

Yr a oydo (old Spanish for ‘going by ear’) rethinks the role of a performer of early music today —who is often limited to playing only what is written in the score— and tries to put into place the creative aspect that the performer not only owns but also shouldn’t avoid.

2. (Brief) Historical Context

Improvisation was more than a common practice in daily music-making during the Renaissance. Spanish musicians of the time provide a brilliant example of this practice. Regardless of the type of publication,[^2] improvisation and glosas —which can be seen as a written reflection of a parallel written improvisational practice— were always present to a greater or lesser extent and demonstrate great excellence and a good deal of inventiveness.

A glance at any of the copious performing directions of these books and, by extension, nearly any 16th-century music book, will immediately reveal an active approach to repertory and music-making. Even a superficial analysis of almost any piece included in the music publications by such eminent musicians as Cabezón or any of the vihuelists (just to mention the Spanish scene) clearly shows a profound urge to —literally— inundate every piece of music which got in the performer’s hands (or ears) with all kind of manipulations, from the simplest embellished versions to the most thoughtful reworking, including the addition of extra lines or the alteration of the original structure of the pieces.

3. An Active Approach

And I don’t say that performers took the liberty to do so or that they allowed themselves to do so:

A widely neglected fact in today’s performance practice is that there are repertories within Western art music (Renaissance music being one of the finest examples) that not only allow but desperately ask for our involvement as performers in every aspect of these creative techniques mentioned above, just as old performers once did.

This active approach, completely alien nowadays, leads us to consider many of these musicians as composers rather than just performers. Certainly, during the Renaissance, the division between these two roles was often unclear, but I would bet many of the crafts we normally associate exclusively with the composer’s work were indeed common tools for most 16th century professional performers.

And it’s just a matter of statistics: I haven’t done the maths, but the number of pieces that underwent these newly-creating techniques within the vihuela or keyboard anthologies was probably quite close to 99,9%. I would even say that if we disregard this fact, our performances would not do justice to the repertory.

4. Our Recipe

More Hispano’s aim (and Yr a oydo is a good example of this) has to do with this active approach described above, taking care not to just play the written notes of the scores —which is today’s common practice– but going one step further:

- Adding another dimension to our interpretation in which we play the same game as early performers —instead of being passive readers— using some of their same tools and resources.

- Creating new melodic phrases, improvised solos, nuances and agogic, never planned in advance, but spontaneously created as a way of punctuating the musicians’ dialogue on stage.

- Playing with open structures that will resolve unpredictably during the course of the performance on stage –or during the recording– taking us on new and unsuspected paths.

Our unique approach to Renaissance music could be summarized in an extremely unusual proposition within the field of early music performance: the fully improvised performance of virtually all the pieces included in our programmes.

So one of our main aims is to show that this creative aspect, at least in the repertoire of the Renaissance and Baroque, is not only a possibility or permission but almost always an inescapable duty of the professional performers: something that is expected of them, distinguishes them and endows them with a clear and marked individuality that makes their interpretations unique while allowing them to develop their own personal non-transferable language… This is exactly what we find in the many ornamental treatises of the 16th and 17th century but what is often lacking in today’s interpretations of this repertoire.

5. The Result

Nowadays, with a varying degree of success, historical repertoires are often approached from a present-day point of view. These present-day tendencies try to modernise the historical repertoire by only adding current musical elements.

More Hispano’s proposal is different

Contrary to this, we opt for a perhaps more arduous task: to recover the art of improvisation by basing it only on the encoded material in the numerous early publications. It is difficult to say if this process can be considered early or modern since the material being used is definitely old, but everything that we now believe is inherently modern, by definition. So it is probably worth taking into account that the so-called early music wasn’t really early at the time of its creation. What we can be sure about is that this kind of approach has hardly been heard by present audiences nor been brought to concert halls.

6. Bye Bye Standards

Yr a oydo is our second recording after eleven years of recording silence. Eleven years of unceasing concert activity in which we have experimented, matured and put into practice ideas, concepts and all the experiences and reflection absorbed during these years.

But if I mention this, it’s only because I consider the change of direction we’ve made with regard to the first album—and with regard to current standards—to be significant. The repertoire has not been chosen according to any composer, style, period or country, nor according to the interpreters themselves (and even less by taking into account any anniversaries or commemorations—despite the lucrative possibilities they use to be accompanied with these days—), but according to what we wanted to show and what we could do with it. It is in this context that improvisation comes into play.

7. Improvisation: A Path Without Way Back

In this recording, for better or for worse, we have at times—freely and consciously—given up one of the parameters of current recording practice: the control and perfection of each and every note. But we have gained elsewhere:

Improvisation brings a range of ingredients to the musical performance — among others a free expression, a rare and amazing ability to communicate with the audience, the underlying risk of (but even more importantly, an opportunity for) creating. And once you experience them, they can get really addictive:

- For the musicians, because of the great possibilities and sensations they get to experience (which are impossible to renounce once you try them);

- For the listeners, as they can surely sense all these elements and as a result, they rush to incorporate them in their own catalogue of personal requirements when enjoying music.

In this way, through improvisation, the performer creates and decides what to play, providing the music with full significance and fluency — barely to be sensed when the interpretation is made exclusively from the written text.

With the spiritedness of the so newly obtained possibility for unpredictable decision and ability to communicate directly with the listener, improvisation becomes the perfect vehicle for the performer’s expressiveness.

At the same time, improvisation enables something vital for any artist, that connects the musicians with their own period of time and that, nowadays, in the field of classical music (and early music by extension), is exclusively reserved for composers: creation.

[^1]: You can also download a pdf version of the booklet, and check out the German translation of the liner notes here, which is also included in the printed version of the new release that just appeared on the occasion of the CD’s new Naxos distribution.

[^2]: Whether theoretical (Tomás de Sancta María’s Arte de tañer fantasía (Valladolid 1565); Francisco Salinas’ De Musica libri septem (Salamanca, 1577), pedagogic (Diego Ortiz’s Trattado de Glosas, Rome, 1553) or purely practical (all pieces included in the numerous vihuela and keyboard collections).